Where do you receive inspiration? Nalina Moses asked the question to nine contemporary residential architects, asking each to choose one residence that had left an impression on them. The following answers were first published on the AIA’s website in the article “Homing Instinct."

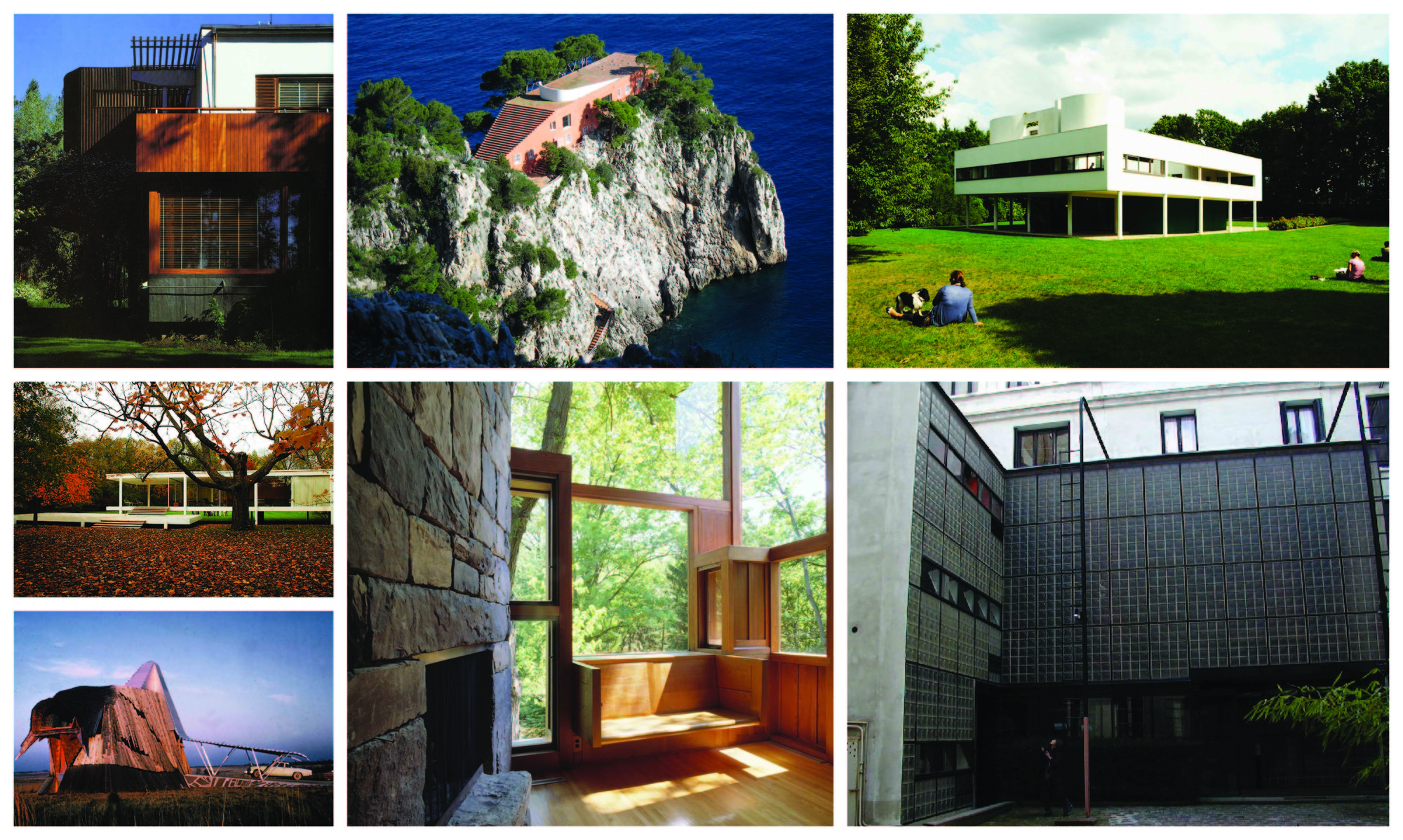

When nine accomplished residential architects were asked to pick a house—any house—that has left the greatest impression on them as designers, most of their choices ran succinctly along the canon of American or European Modern architecture. Two—Alvar Aalto’s Villa Mairea and Pierre Chareau’s La Maison de Verre—were even tapped twice.

If the houses these designers chose weren’t surprising, the reasons they chose them were. Rather than groundbreaking style or technologies, what they cited were the moments of comfort, excitement, and refinement they offered: the restful proportions of a bedroom, the feel of a crafted wood handrail, an ocean view unfolding beyond an outdoor stair.

Several said they’d like to live in the house they selected; one admits that he’s frightened by the possibility of giving himself over to such a surreal, otherworldly environment. More than masterpieces, these houses are remembered as complex, vivid environments that transcend mundane patterns and rituals with subtle grace or otherworldly gusto.

Notions of Speed and Time

Villa Savoye, Poissy, France, by Le Corbusier, 1928

EB Min, AIA

Min | Day, San Francisco and Omaha, Neb.

I think seeing the house in person made it much more apparent that, instead of a series of contained spaces, the house was really a continuous unfolding experience. I had not been in anything like the Villa Savoye before, and [I] experienced a house designed around circulation—so outward-looking rather than inward. The spiral circulation, openness to the exterior, and integration of gardens and terraces was and is very compelling for me.

The house reflects the impact of automobile travel, and how important ideas of speed and motion were at the time the house was designed. There are obvious references to the car, like the curve of the ground floor that is designed around the turning radius of [a] 1927 Citroen. But the house also reflects these new ideas in deeper ways. The ribbon windows frame views of the landscape that are fleeting, almost cinematic.

In a way, houses are like fashion. Their design is very personal, requires emotional investment, and reveals a lot about people’s cultural interests. At the time that Villa Savoye was built, people’s ideas about space and time were changing radically. That’s evident even when you look at the house today.

A Place People Touch and Love

Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto, Noormarkku, Finland, 1939

Peter Bohlin, FAIA

Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

When I look back, I see that the houses that have interested me most are those that relate brilliantly in both conception and detail to the people who live there, and the world that surrounds them. The house that has been as powerful in my mind as any is Alva Aalto’s Villa Mairea, which I visited when I was a young architect. This is a refined, quite personal summer home which was designed for discerning and encouraging clients around the time I was born, 1937.

The house is approached through a pine forest, its entry marked by a sheltering canopy that’s both Modernist and made from wood, a reminder of the trees. The nicely detailed wood front door’s hardware wants to be touched. Almost too refined, the interior is beautifully elaborated with a stair that I wished to climb, railings I wanted to touch—a light-filled space. These have always been reminders to me of the pleasure of making places people often touch and love.

Behind these elegant spaces is a sunny outdoor garden and a lovely free-form pool—a contrast to the dark pine forest beyond. But perhaps best of all was a wood sauna near the pool under a low grass roof, supported by round turned wood columns wrapped together. The architecture of the house is a graceful Modernism transformed by Aalto’s very personal sensibilities and a form of rusticism.

A Place You Would Never Tire Of

Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto, Noormarkku, Finland, 1939

David Salmela, FAIA

Salmela Architect, Duluth, Minn.

I can think of many iconic Modern houses that I love, which tend to be ideological artistic structures, but Villa Mairea seems to be all that and much more. It is a house that feels like a home you would never tire of living in.

In this house, Alvar Aalto reintroduced a familiar quality from the past Finnish vernacular into his evolving Modernism. He let materials evolve to their functional needs, rather than a singular monolithic appearance. The richness of that thought starts from the interior and radiates out to the exterior. Materials vary from fine detailed wood, whitewashed masonry, to moss-covered, dry-laid stone walls. The colors vary from white to black, with various [aged] wood in between. This is a building that changes with every turn of a corner but is always meaningful and harmonious.

This is a building that seems to age well. This overall logic is still valid today, but certainly needs to be applied to a culture and a specific place. I take this as Aalto’s goal to set an example of what a Modern house should be.

A Weekend Getaway

Farnsworth House by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Plano, Ill., 1951

Robert M. Gurney, FAIA

Robert M. Gurney FAIA, Washington, D.C.

I visited the Farnsworth House several times. One particular time, I was the only person [on the] tour and was able to spend several hours exploring the house with only the tour guide present.

The house supports living in an environment that is serene and calming. It provides a physical and psychological escape from the busy, hectic lives that we all experience. The house is designed with free flowing, open spaces and with uninterrupted walls of floor-to-ceiling glass, reducing the sense of enclosure to a minimum. Unenclosed floor planes extend the living area and further enhance the relationship between the interior and the landscape.

The house was intended to be a weekend retreat and serves that purpose perfectly. I would be comfortable living in this house, but not as a primary residence. I personally prefer to live in a vibrant urban environment. But I would love to have a retreat in a beautiful remote location like this.

Intensifying Place

Casa Malaparte by Adalberto Libera, Isle of Capri, Italy, 1937

Matthew Kreilich, AIA

Snow Kreilich Architects, Minneapolis

The house is perched on a narrow, rugged limestone peninsula above the Gulf of Salerno. It is only reachable by foot or by boat. My wife and I choose to hike the island’s edge in search of the home, along a small winding path and under canopies of orange trees. The first spotting of the home was breathtaking. The home’s warm Tuscan orange stucco and brick skin creates a striking contrast against the blue waters below.

The most powerful element of the home is the inverted pyramidal stairs leading to the rooftop patio, which overlooks the water 30-plus meters below. This singular move both works with the existing topography, but also allows access to uninterrupted views to the horizon. The interiors are simple and straightforward. The main living space has a grand fireplace which one can view through to the gulf beyond.

The home’s relationship to its site is one of the best examples of architecture’s ability to intensify one’s understanding and experience of place. The house offers a sense of relaxation and calm, as it allows for an occupant to be fully immersed in the surrounding landscape. The remoteness of the house adds to the intimacy of the experience. I would like to retire there.

Every Condition and Connection is Different

La Maison de Verre, by Pierre Chareau, Bernard Bijvoet, and Louis Dalbet, Paris, 1932

Anne Fougeron, FAIA

Fougeron Architecture, San Francisco

Pierre Chareau didn’t build many houses, but he completed a number of Parisian apartment interiors. So you can see that in La Maison de Verre, the interior is incredibly rich. Almost all of the furnishings are built-in cabinets and all of the cabinets operate in different ways. Many of the cabinets function as room dividers, so the space itself can be used in different ways. There’s a bookshelf that also serves as a guardrail to the stairs behind it. It’s built with wood inserted into a metal frame. And there’s a cabinet in the bathroom made from perforated metal that can be rotated to act as a screen. These are ideas about materiality and flexibility that we’re still playing with today.

The house is very modern and also very crafted. The space inside is open with a dramatic two-story living room space, with a glass-block wall facing the interior courtyard. This was one of the first times glass block had been used in a residential application. The interior has a complexity in detail and a deep understanding of materiality that makes me believe Chareau didn’t draw all the details but worked them out with very skilled craftsmen on site. It’s a complex interior. There’s no repetition: Every condition and connection is different.

What it Means to be a House

La Maison de Verre, by Pierre Chareau, Bernard Bijvoet and Louis Dalbet, Paris, 1932

Tom Kundig, FAIA

Olson Kundig Architects, Seattle

About 10 years ago I had the good fortune to visit Maison de Verre in person. It had a strong and immediate influence on me. It gave me a sense of confidence about what a house could be, both conceptually and at the level of craft and detail.

Beyond those aspects, there’s the cultural and poetic, prospect and refuge, inventiveness—essentially Maison de Verre is an exploration of what it means to be a house. It explores all those things and builds upon tradition. The Latin root of the word “tradition” means to surrender or to give over—basically it’s about accepting rather than exploring. Ultimately it’s about shelter, but it embodies so much more: notions of yin and yang, both tectonic and poetic ideas. It’s practical, yet expressive. It provides everything you need, from shelter to culture.

Two Different Lives

Fisher House by Louis Kahn, Hatboro, Pa., 1967

Daryn Edwards, AIA

Blackney Hayes Architects, Philadelphia

This house is on a suburban street, surrounded by typical suburban houses from the early- to mid-20th century. It’s on a beautiful plot, with a stream that runs through the backyard. The house is basically composed of two juxtaposed cubes. The slightly smaller one holds the living room, dining room, and kitchen, and the larger [one] encompasses the entry, the bedrooms, and bathrooms.

The proportions of the inside spaces, and how they shape your experiences, are what’s most amazing about it. The openness of the floor plan and the high proportions of the rooms in the public areas of the house give it a light Modern feeling that’s very different, for example, from the Philadelphia row house where I live. The Fisher House has large windows and raised ceilings that bring the outside into the gathering areas, but that offer privacy in the bedrooms.

There’s a comfortable, intimate feeling to the more private parts of the house. The bedrooms seem well-proportioned, but it would be uncomfortable for more than one or two people to stand inside them at once. On the other hand, the house’s more public spaces—the living and dining rooms—would be just right for a party or other event with dozens of people. The house supports both of these kinds of living.

Standing Up to the Landscape

Prairie House by Herb Greene, Norman, Okla., 1961

Brian Phillips, AIA

ISA Architecture/Research, Philadelphia

I first drove up to the house and walked around it when I was an architecture student. At that time the house seemed to me like it landed from another planet—adventurous and experimental. Its whimsical form, combined with the deployment of everyday materials in novel ways, impresses me the most. I love the oversized fixed window at the top and the wonderful light-metal canopy in front that calls out a strong sense of entry.

This house taught me everything I know about the idea of context, its complexity, and multiple readings. In a straightforward way, the house references the prairie grouse—a local Oklahoma bird—but, more importantly, it seems to struggle for attention against the overwhelming homogeneity of the tall grass prairie landscape. While urban buildings can make subtle moves to find identity, the Prairie House needed to show its aggressive plume to stand against the relentless minimalism of the prairie landscape. It takes a lot of visual energy to stand up to that ocean of simplicity.

The house is a small retreat-type home. I’m not completely sure what kind of people would live inside, or how they would live. I’m not sure I could live inside. The house simultaneously entrances me and scares me. If I could make it through a night, I could probably stay forever.